Working Hard So They Won’t Have To

There are some challenges that people in my line of work see over and over again, but that usually lie somewhere beneath the surface.

We’re talking about transitioning family wealth from one generation to the next in a productive and meaningful way, which is so challenging because the creation of the wealth and its eventual transition typically occur in very different contexts.

Most wealth creators began from a place of scarcity and true need to do something to put food on their literal and figurative tables.

Decades later, when they get around to planning for the transition of that wealth to their heirs, those conditions are quite far in the rear view mirror for them, and possibly nowhere in the memories of those heirs.

Unfortunately, the value of “industry” does not always fall close to the tree.

A Confluence of Client Situations Creates a Spark

Some version of this challenge is percolating to the surface with a few clients with whom I’m currently working, which is what made it a salient subject for a blog post.

I wanted to find a phrase that captures it well, and settled on the “value of industry”.

It’s not perfect, but I like the fact that it leans towards a much less common use of the word “industry” than we usually come across.

I often share Google search results here, and now they arrive in the form of an AI summary, to wit:

“When used to describe a person, “industry” signifies diligence, effort, and a persistent habit of working hard.

It implies a dedication to work and a strong commitment to achieving goals through sustained effort.”

Every hardworking wealth creator I’ve ever met hopes that this part of their DNA will live inside each of their offspring and all future generations.

Many end up disappointed.

Big Safety Net – Pros and Cons

Quite simply, most rising generation members of wealthy families become accustomed to living with a large safety net.

Many of those who don’t suffer from this are those whose parents worked extra hard to hide their true financial wealth exactly because of this fear. But that method comes with its own set of drawbacks.

The word “entitlement” may be front and center as you read this. I’ll remind you that children become entitled in large part because of how they are raised. Entitlement Road is a two-way street.

Parents all say they don’t want their offspring to be entitled, and then many unwittingly parent them in ways that foster it.

The safety net is good, as most things with “safety” in their name are, but the other side of it is that it almost can’t help but erode the “industry gene’s influence” on how people choose to live their lives.

No Simple Solutions

I like to think that regular readers are used to the fact that I rarely provide simple solutions to the many challenges I share here weekly.

I sometimes talk about parents instilling a love of business to their rising generation, rather than a love of the specific family business they are currently involved in.

If everyone in the family has the “entrepreneur gene”, this can work well.

But societal norms are a huge headwind for many parents in their 60’s whose thirty- and forty-somethings do not value the 70-80 hour weeks of years gone by.

As I write this, I just received an email with the subject line, “Why younger clients want to retire early”; I could not make this up.

I know that the elders worry that their preteen and teen grandkids are getting a much different household vibe around the value of a job at which one toils for most of their adult life.

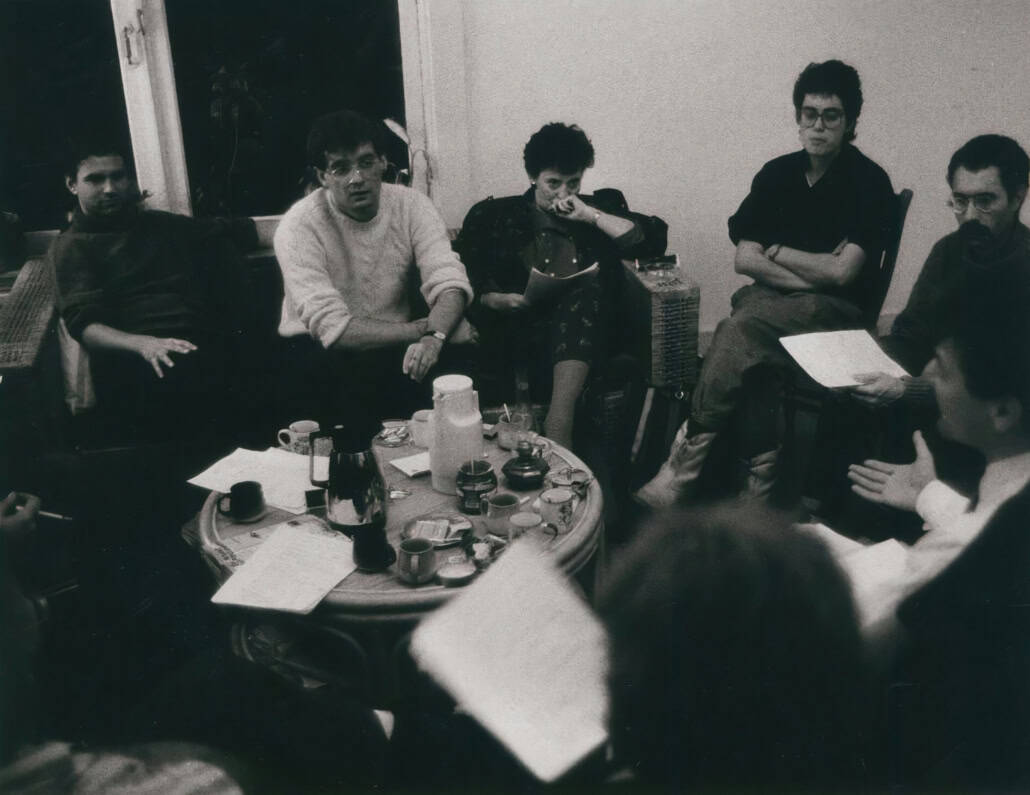

Sharing Stories and Co-Creating a Future

One thing I do know, though, is that parents lamenting this and keeping it to themselves isn’t usually helpful.

But regularly complaining about it in a judgemental way as a method to counteract it isn’t any better.

Perhaps the best antidote is regularly meeting as a family and talking about such matters, in and adult-to-adult fashion.

Sharing stories about hard work and its benefits and trying to help co-create a future in which this value of industry is a worthwhile pursuit for all family members can help normalize it as a laudable family trait.

It’s better that ignoring it or complaining about it.